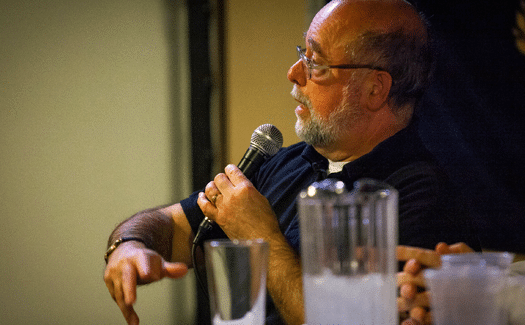

A leading expert in child death investigations talks about his unlikely career.

A parent’s response to grief comes in many forms. And, after decades as a medical examiner, Dr. Thomas Andrew, among the country’s leading experts on child death, knows all about that.

Andrew is New Hampshire’s former chief medical examiner and spent decades conducting autopsies and describing to loved ones, often parents, about why somebody died.

Some are angry. Unlike in television crime shows, autopsies often don’t uncover an exact cause of death. In the case of one 15-month-old, however, Andrew did. An immune disorder that led to a widespread infection killed the child. But the parents, recent Russian immigrants who didn’t understand IVs and technology, didn’t believe it.

“They were convinced the child was killed by some sort of fluid mismanagement in the hospital,” Andrew said. “What I was trying to get across to them, which was hugely important, is that it’s a genetic disease. They needed genetic counseling. They need to strongly consider family planning going forward, but they were having none of it.”

In other cases, from the depths of their grief, they find unbelievable kindness. Andrew still gets emotional talking about the case of a seven-year-old boy who died during a pick-up basketball game. Andrew’s autopsy revealed that the boy had an undiagnosed congenital heart condition.

“When I called his father, and I explained what the findings were, he said, ‘Doc, I don’t know how you do this day after day,’ and he said, ‘How are you doing?’” Andrew remembers. “I just fell off my chair. Even as I tell the story now, I can’t believe he found the strength to ask that question. I just wanted to say, ‘Are you kidding buddy? Don’t think about me.’ That was an amazing, amazing experience.”

In his decades talking to mourning parents, “if you can imagine everything in between those two extremes,” he said, “I’ve seen it.”

An unlikely move

Andrew didn’t set out to spend his career analyzing why somebody died. It began with the goal of helping young people live. Fresh out of medical school, Andrew worked as a pediatrician — and loved parts of it, especially interacting with the kids.

“They bring so much to the table,” he said. “They are such intellectual sponges and are really curious about everything.”

But he didn’t enjoy the frenzied daily pace of ear checks and camp physicals. “I’m a plodder by nature,” he said. “I like to look at things from many different angles, and that didn’t fit with that model.”

At the same time, the cases that really engaged his intellect as a pediatrician were those that included aspects of forensic medicine, such as Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, consumer product safety issues and incidents of neglect.

Forensic medicine wasn’t a new topic for him. In medical school, a series of lectures in a basic pathology class captivated him and, as a senior, he completed a pathology rotation. Eventually, he made the switch to forensics.

Trying to answer, ‘Why?’

The job shifted from dealing daily with the living to studying the dead and explaining to their loved ones why they died. Andrew’s career took him from Ohio to New York City and, in 1997, to New Hampshire. Before retiring in 2017, he had conducted more than 5,200 autopsies to explain a sudden, unexpected or violent death.

And, with his training and work as a pediatrician, he carved out what he calls “a bit of a niche” in child deaths, focusing some of his writings on the topic. Today, Andrew’s White Mountain Forensic Consulting Services specializes in reviewing medical records and autopsies and testifying about deaths in criminal and civil cases.

Throughout his career, there was a common frustration: He couldn’t uncover why a child had died, yet he knew a family was desperate for answers.

In New Hampshire, parents often had two questions: Why did my baby die? And will this happen to my next one? They were queries that Andrew, many times, couldn’t fully answer.

But, despite their anguish and a lack of clear-cut answers, he said, it’s critical for medical examiners to be intellectually honest with families.

“To feel like you haven’t helped that family is a really empty and desolate feeling, but there is nothing crueler than a kind lie,” he said. “You’ve got to be totally honest with people when you don’t know those answers.”

And when they deliver their discoveries to families, medical examiners must be prepared to tailor their message to their audience. Empathy, he said, is critical in every conversation. If they can’t be sensitive to a specific family’s needs, they need to find a social worker or grief counselor who can. “They do more harm than good by being a bull in a china shop,” he said.

For families who seek answers, Andrew said their path doesn’t have to end with an inconclusive autopsy. He encourages parents to send their child’s case to researchers and groups, such as the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Project, who are investigating particular health issues and causes of death.

“That’s what’s going to get answers sooner than later,” he said.

Finding the ‘trifecta’

These days, when he’s not testifying in a court case or reviewing medical records, Andrew is working on a master’s degree in divinity. He hopes to eventually become the full-time chaplain for the Daniel Webster Council of the Boy Scouts in New Hampshire. Both his faith and his involvement in Boy Scouts have provided a necessary relief from the seriousness of his day job.

And, after years of uncovering what bad decisions may have killed a person — whether it was drug abuse, dangerous driving or other unhealthy lifestyle choices — he’ll get to be on the front end of public health, providing tools for young people to help them make better decisions.

“Guiding these young people to make moral and ethical decisions, not only for their own sake, but the sake of others, it’s the trifecta,” he said. “I’ll get to do all these things that I love.”